Piaget’s Theory Of Development

The Definitive Guide

Have you ever wondered how different children develop differently and what is the main reason behind it? Truth be told, there isn’t one specific reason behind this developmental divergence. However, there are many viable theories that speculate this very efficiently.

One such theory is Piaget’s Theory of Development. This theory is very well thought-out, thus making it one of the most relevant theories in child development. In this article, I will:

- Deconstruct Piaget’s Theory of Development

- Discuss the four stages of Piaget’s Model

- Breakdown the strengths and weaknesses of the theory

- Unravel ways to use Piaget’s theory for coaching

And much more!

So, what are we waiting for? Let’s get straight into it!

Don’t have time to read the whole guide right now?

No worries. Let me send you a copy so you can read it when it’s convenient for you. Just let me know where to send it (takes 5 seconds)

Yes! Give me my PDFContents

Chapter 1:

History of Piaget’s Theory of Development

First and foremost we need to understand who Piaget was and the basics of his theory. This is exactly what we will be doing in this chapter. We will look at Piaget and his theory’s origin.

This chapter should help set the fundamentals of this theory clearly for you to then build upon it as we progress through the article.

Origin of Piaget’s theory

Jean William Fritz Piaget, a Swiss psychologist best known for his studies of child development, lived from 9 August 1896 to 16 September 1980. Genetic epistemology refers to Piaget’s theory of cognitive development and epistemological perspective as a whole.

Piaget gave the education of children a lot of weight. He stated in 1934 that “only education is capable of saving our society from possible collapse, whether violent or slow” while serving as the Director of the International Bureau of Education.

In pre-service education programs, his theory of child development is covered in a detailed manner. In fact, educators are still using constructivist-based methods.

While serving as a professor at the University of Geneva, Piaget founded the International Center for Genetic Epistemology in Geneva in 1955. He served as its director until his passing in 1980.

The Center is sometimes referred to as ‘Piaget’s factory’ in the academic literature due to the sheer volume of collaborations that its foundation made possible and their significance.

Piaget was “the outstanding pioneer of the constructivist theory of knowing,” according to Ernst von Glasersfeld. However, it wasn’t until the 1960s that his ideas started to catch on.

As a result, psychology’s primary subdiscipline of development research began to take shape. By the end of the 20th century, B. F. Skinner and Piaget were the two psychologists who had received the most citations.

How did Piaget come up with the theory?

Piaget “was struck by the fact that children of different ages made different sorts of mistakes when completing problems” in 1919 while working at the Alfred Binet Laboratory School in Paris.

His hypothesis of cognitive development was based on his experiences and findings at the Alfred Binet Laboratory. He thought that the “quality rather than amount” of children’s intelligence caused them to make different mistakes depending on their age.

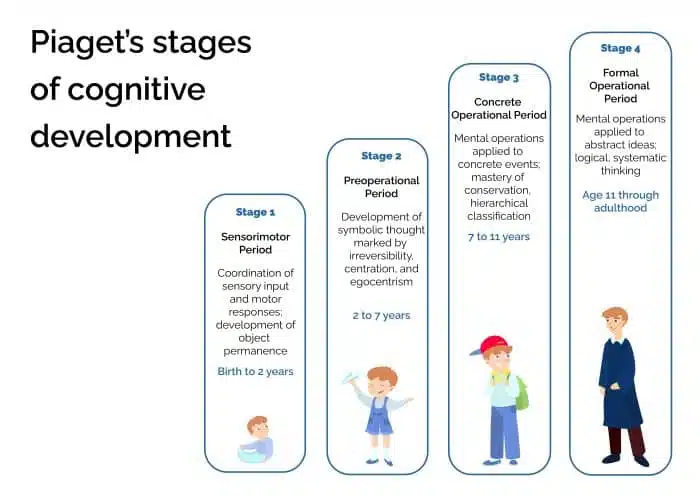

According to Piaget, children go through four phases of development: the sensorimotor stage, the preoperational stage, the concrete operational stage, and the formal operational stage. Every stage describes a particular age range.

He described the stages of cognitive development in children. He thought that children, for instance, experience the world through actions, describing things with words, thinking logically, and using reasoning.

According to Piaget, biological maturation and environmental experience led to a gradual rearrangement of the mind’s workings.

He believed that kids develop an awareness of the world around them, encounter gaps between what they already know and what they learn from their surroundings, and then revise their views as necessary.

The human organism, in his opinion, is centered on cognitive development, and language development is dependent on the knowledge and understanding that are acquired through cognitive growth. The initial works of Piaget attracted the most attention.

Direct implementations of Piaget’s ideas include “open education” and child-centered classrooms. Despite its enormous success, Piaget’s theory has significant flaws that he himself acknowledged: for instance, it favors abrupt stages over continuous growth (horizontal and vertical décalage).

What does Piaget’s Theory of Child Development outline?

The stages of a child’s cognitive development are described by Piaget. Changes to the cognitive process and abilities occur during cognitive growth.

According to Piaget, early cognitive development entails action-based processes that subsequently lead to modifications in mental processes.

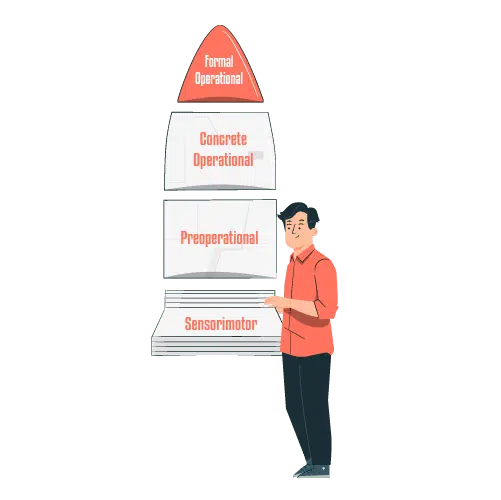

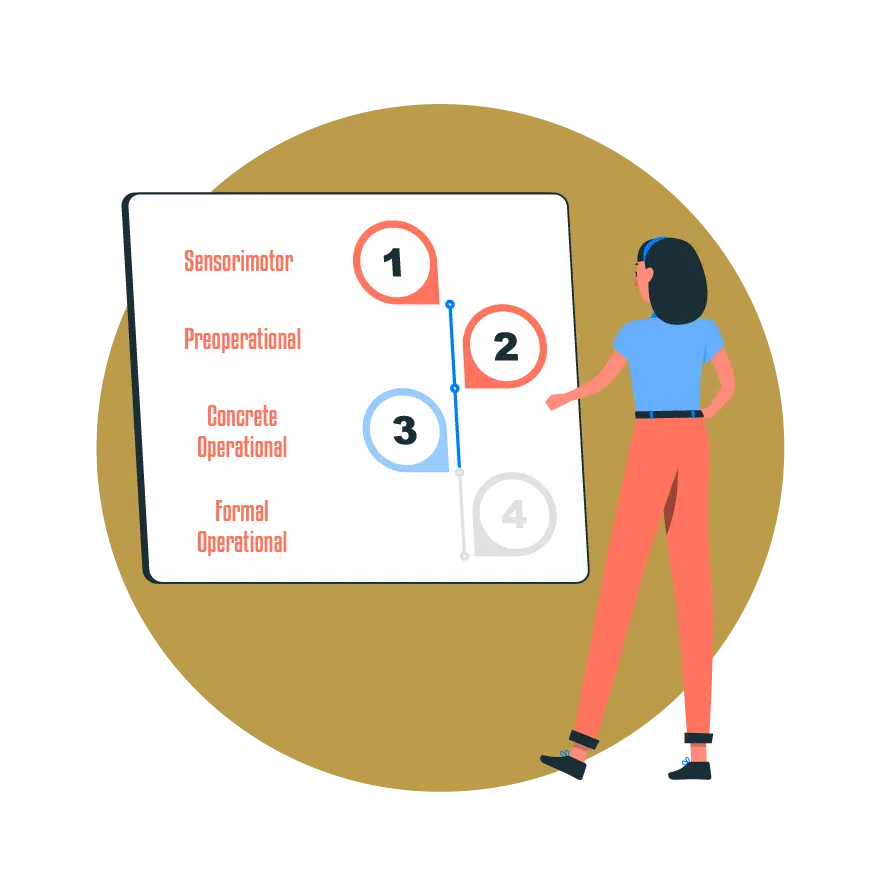

Jean Piaget proposed four developmental stages for humans in his theory of cognitive development: the sensorimotor stage, the preoperational stage, the concrete operational stage, and the formal operational stage.

What are the four stages of the theory?

Piaget’s theory of cognitive development proposes 4 stages of development.

Stage 1: Sensorimotor stage – Birth to 2 years

Stage 2: Preoperational stage – 2 to 7 years

Stage 3: Concrete operational stage – 7 to 11 years

Stage 4: Formal operational stage – ages 11 and up

The sequence of the stages is universal across cultures and follow the same invariant (unchanging) order. All children go through the same stages in the same order (but not all at the same rate).

Piaget’s Observations that Led to the Theory

In the 1920s, Piaget worked at the Binet Institute where his responsibility was to translate English intelligence test questions into French. He got fascinated by the explanations kids provided for their incorrect responses to questions requiring logical thought.

He thought that these wrong responses demonstrated significant disparities between how adults and children think.

With a fresh set of presumptions regarding young children’s intellect, Piaget struck out on his own:

- The quality rather than the quantity of a child’s intelligence is different from an adult’s.

- This implies that youngsters reason (think) and perceive the world differently from adults.

- Children actively increase their world knowledge. They are not mindless creatures who sit around waiting to be educated.

- It was better to consider things from a child’s perspective in order to comprehend their rationale.

Piaget was not interested in evaluating children’s I.Q. by how well they could spell, count, or solve problems. He was more intrigued by how essential ideas like the concept of a number, time, quantity, causation, justice, and so forth came into being.

Piaget used controlled observation and naturalistic observation of his own three infants to study children from infancy to adolescence. He derived these for his journal entries that tracked their growth.

Additionally, he conducted clinical interviews and made observations of older kids who could understand inquiries and carry on dialogues.

Super fascinating, right? Trust me it gets even more interesting as we learn more about this theory. Let us do just that in the following chapter where we will understand the nitty gritty of the four developmental stages outlined by Piaget.

Chapter 2:

The Four stages of Piaget’s Model

We have a good understanding of Piaget’s background and thought process but let us now dive deeper into the four stages of development as theorized by Piaget.

We will progress through the stages chronologically and also understand the major characteristics of each stage in this chapter.

Stage 1: The Sensorimotor Stage

The first stage of a child’s cognitive development is the sensorimotor stage. Children primarily learn about their surroundings throughout this period through their senses and motor activity.

Six substages make up the sensorimotor stage, during which children’s behavior transitions from being reflex-driven to being more abstract. Each substage is briefly explained.

There are six major changes and development characteristics in this stage which I will break down for you one by one.

1. Reliance on reflexes (0–2 months)

Children typically employ their reflexes at this point. They are unable to combine data from all of their senses into a single, coherent idea.

2. Initial circular responses (1–4 months)

Children begin to combine data from several sensory organs. They begin acting in a way that meets their wants or the way their bodies are feeling. For instance, they mimic rewarding actions and modify their behavior to ingest food from various sources. When they hear or see anything, they turn to react.

3. Secondary reciprocal effects (4–8 months)

Children’s actions become more deliberate, and the repertoire of behaviors they repeat broadens to include those that elicit fascinating effects outside of their own bodies.

They might operate the buttons of a toy, for instance. Children also begin to show an increased interest in their surroundings. They repeatedly engage in actions that elicit interesting reactions.

4. Coordinating auxiliary plans (8–12 months)

By this time, kids’ actions are increasingly goal-oriented, and they can combine actions to accomplish goals.

5. Tertiary circular reactions (12–18 months)

Children experiment with various behaviors and actions to get diverse results rather than repeating the same ones.

These actions are deliberate and not accidental or spontaneous. Children can integrate increasingly complex behaviors and even carry out a behavior similarly but not exactly to get the desired outcome, unlike primary and secondary reactions.

6. Mental jigsaw puzzles (18–24 months)

Children begin to rely on mental abstractions to solve issues, use words and gestures to express themselves, and are capable of pretending.

Children can ponder and carefully select their activities rather than depending on repeated attempts to solve issues or riddles.

Stage 2: The Preoperational Stage

Children begin to use mental abstractions as they reach the end of the sensorimotor stage.

Children begin to employ mental representations rather than the physical appearance of items or people when they are two years old when they enter the preoperational stage.

In this stage, playing pretend and chatting about things that happened in the past or with other individuals who aren’t present are two instances of abstract representations.

During this stage, other intriguing cognitive developments take place. Children, for instance, comprehend causation. Children also grasp that despite differences in appearance, things and individuals retain their identities. For instance, a caregiver dressing up as Santa Claus might not be as convincing at some point during this stage.

Children continue to learn more about categorization at this stage. They can group things according to their similarity or distinction. Additionally, they begin to comprehend quantity and numbers, including words like “more” and “larger.”

In the preoperational stage, abstract thought develops quickly, but other cognitive processes take longer to mature.

For instance:

- Children frequently take into account their own points of view.

- Children don’t comprehend that two things might be similar even when they seem to be different (more about this in the next section on Conservation).

- Children have trouble understanding another person’s perspective.

Stage 3: The Concrete Operational Stage

The following stage, which starts at age seven, is the concrete operational stage. Children at this age are better able to solve difficulties since they can weigh several possibilities and viewpoints.

At this stage, all of their cognitive faculties are more fully developed. The following prominent changes are observed:

- Children’s categorization skills advance when they learn how to arrange objects along a dimension comprehend that categories contain subcategories, and connect two objects using a third object.

- Their arithmetic skills significantly advance, and they are able to carry out increasingly challenging mathematical operations.

- They have higher spatial skills. They are more accurate in determining distance and time.

- They are able to read maps and explain how to get from one place to another.

The biggest characteristic of this stage is ‘conservation’. Conservation is the concept that something can still remain the same even if it appears to be different. Children are better able to solve conservation-related issues at this time because they have a greater understanding of the notion of conservation.

An illustration would be pouring a cup of water into two cups. While the other glass is short and wide, the first is tall and thin. Understanding of conservation can be seen in the fact that both glasses contain the same quantity of water.

Children that are still developing deal with conservation issues. They have difficulty, for instance, with tasks when the following is conserved even though it looks to be different:

- Quantity of items (e.g., two sets of 10 items arranged differently)

- The liquid’s volume (e.g., the same volume of liquid in two differently shaped glasses)

Children have difficulty conserving since they can only fix their attention on one dimension at a time. For instance, when determining the volume of a liquid, they can only take into account the form of the glass and not both the shape and the volume of the liquid.

Additionally, they do not yet comprehend reversibility. The concept of irreversibility describes a child’s incapacity to mentally undo an activity and return a thing to its original state.

For example, pouring the water out of the glass back into the original cup would demonstrate the volume of the water, but children in the preoperational stage cannot understand this.

Children who are in the concrete operational stage, however, can address conservation issues. This is a result of the following cognitive capacities that youngsters now possess:

- They are aware of reversibility (i.e., items can be returned to their original states).

- They are able to decenter (i.e., concentrate on multiple dimensions of items, rather than just one).

- They are more aware of identity (i.e., an item remains the same even if it looks different).

Stage 4: The Formal Operational Stage

Children begin the formal operational stage at the age of 11.

This phase is characterized by abstract thought. Children are not constrained by the present and are able to think about abstract ideas.

They can conceive of hypothetical circumstances and other possibilities, such as those that do not yet exist, might never exist or might be improbable and fantastical.

Children can use hypothetical-deductive reasoning at this age to test hypotheses and make inferences based on the findings. Children at the formal operational stage can use their reasoning abilities to apply increasingly complex problems in a systematic, logical manner, in contrast to younger children who approach problems randomly.

Major characteristics and developmental changes during this time such as:

- Begins to think abstractly and reason about hypothetical problems

- Begins to think more about moral, philosophical, ethical, social, and political issues that require theoretical and abstract reasoning

- Begins to use deductive logic, or reasoning from a general principle to specific information

Wow! That was a lot of information but doesn’t it make so much sense? I, for one, have a vague remembrance of these stages when I saw children in my family progress through each of them. But, never before have I observed them so keenly.

Now that we know the four stages in detail, let us try to understand what are schemas related to these stages and what are they used for in the next chapter.

Chapter 3:

Children’s knowledge of the world has advanced since they were two years old, but there has also been a fundamental shift in how they view it.

Piaget proposed a number of variables that affect how kids learn and develop, and these are what fit into the general psychological idea of ‘schemas’.

Schemas Related to the Four Stages

A schema summarizes the mental and physical processes necessary for comprehension and knowledge. Schemas are categories of knowledge that aid in our interpretation and comprehension of reality.

According to Piaget, a schema encompasses both a category of knowledge and the way that it is acquired.

As experiences unfold, this fresh knowledge is applied to alter, supplement, or add to pre-existing schemas.

For instance, a young toddler might have a schema about a certain kind of animal, like a dog. A child might think that all dogs are little, fuzzy, and four-legged if their only exposure to them has been with small dogs.

Let’s say the youngster comes upon a large dog. The child will take in this new information, modifying the previously existing schema to include these new observations.

Types of Relevant Schemas in Piaget’s Theory

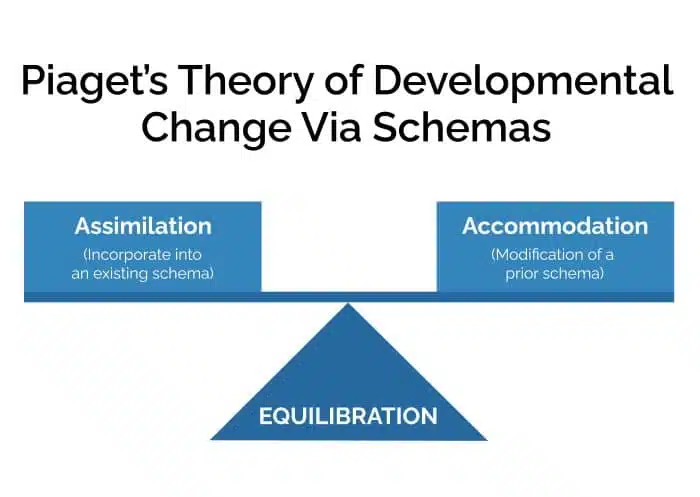

Assimilation, accommodation, and equilibration are the three types of schemas in Piaget’s Theory. I will walk you through each one in detail in this section.

- Assimilation

Assimilation is the process of incorporating new information into our preexisting schemas. Because we frequently alter experiences and information to suit our preexisting beliefs, the process is partly subjective.

Assimilation of the animal into the child’s dog schema occurs in the aforementioned example when the toddler sees a dog and calls it a “dog.”

- Accommodation

The capacity to modify pre-existing schemas in light of fresh knowledge is a crucial component of adaptation. This method may also result in the creation of new schemas.

- Equilibration

It’s crucial to strike a balance as children advance through the phases of cognitive development between assimilation—applying prior knowledge—and adaptation—adjusting behavior (accommodation).

According to Piaget, every kid tries to find a happy medium between assimilation and accommodation through a process he dubbed equilibration. Equilibration explains how kids can progress from one level of thought to another.

These schemas help add another layer of relevance to the already well-thought-out theory of development by Piaget. Every model has its strengths and weaknesses alike. In the next chapter, I will discuss the limitations and advantages of Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development.

Chapter 4:

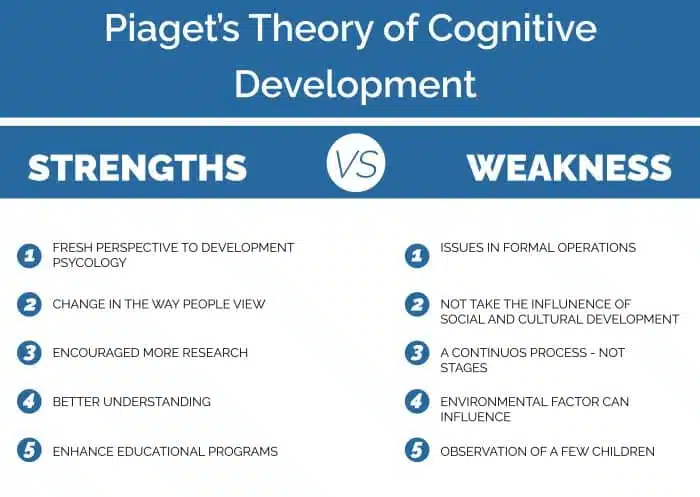

Strengths and Weaknesses of Piaget’s Theory

Piaget’s theory had established the difference in the way children and adults perceive and use information. However, it has some shortcomings, including overestimating the ability of adolescence and underestimating an infant’s capacity. In this chapter, I will be walking you through the various strengths and weaknesses of Piaget’s Theory.

What are the strengths of Piaget’s Theory?

One of Piaget’s major strengths is that it established the difference between how children and adults perceive and use information.

Educators and social workers, according to this theory, can assess children’s development, compare it to what is considered a norm under Piaget’s theory, and offer interventions to allow the development of the necessary capabilities.

Furthermore, while contemporary researchers and practitioners criticized Piaget’s work, it was instrumental in establishing the study of cognitive development and advancing modern child psychology.

As a result, while more research is needed to promote Piaget’s work and account for various social and cultural contexts, this theory provides a foundation for understanding how children’s cognition develops.

What are the limitations of Piaget’s Theory?

Piaget’s theory has some imperfections, including overestimation of adolescent ability and underestimation of infant capacity. Piaget also overlooked the importance of cultural and social interaction in the development of children’s cognition and thinking abilities.

Furthermore, the theory is abstract and relates to the process of thinking, making it difficult to test and evaluate. The process of cognition cannot be directly observed and measured.

Instead, researchers employ tests for indirect measurement and assumptions. This implies that there may be discrepancies between theory and practice.

Piaget’s work, in any case, provides an outline or model of how a child should develop and allows one to understand how children and adolescents process information.

It assists social workers in assessing a child’s development and incorporating strategies to help them develop the cognitive abilities they will require in the future

In the last chapter of this informative guide, I will discuss how you can apply Piaget’s theory to help your clients as a coach.

Chapter 5:

Using Piaget’s Theory for Coaching

In this chapter, we are going to gradually stray away from the theoretical outlook of this theory and focus more on practical application.

I am going to answer all the relevant questions you may have on how to use this theory effectively in coaching clients. So, let’s work through it together.

Can coaches use this theory?

The answer is a loud yes. This theory was developed to better understand the various developmental stages during childhood to eventually assist children to create the best version of themselves.

Coaching is a powerful tool that can be used to shape the lives of children right from childhood. Thus, adding this robust theory to your coaching sessions will not only make your sessions more impactful but also give you a whole new perspective while understanding your clients’ thought process and behavior.

With whom can coaches use this theory?

The theory focuses on the developmental stages of children and thus it is most appropriate to use it for children-especially between the ages outlined by Piaget. Coaches that have young-aged clients can benefit a lot from grasping this theory.

However, another important and slightly broad usage of this theory is to use it as a tool to understand childhood trauma and the developmental processes of adult clients.

Many issues that coaches try to resolve in coaching stem from early childhood problems that clients might have faced. Thus, knowing and understanding this theory helps us to understand during which developmental phase a client might have developed harmful patterns.

Additionally, we can use this knowledge to design better coaching sessions that are based on healing the said pattern.

Do coaches need any certifications to use this theory?

Since this is a theory, it is regarded as widely available knowledge and there aren’t any specific courses that focus on certifying people just regarding Piaget’s theory.

Here are some courses I recommend if you wish to gain relevant certifications to become more credible as a coach such as:

- Certificates regarding early childhood development

- Certificates of coaching

- Certificates or degrees of psychology

- Certificates of childhood counseling

- Any other relevant coaching certifications

You can even have a combination of these certifications. Remember though that becoming a certified coach isn’t mandatory. It simply adds to your credibility but it’s not a necessity.

Ways of using this theory in coaching

Some educational implications of this idea include the fact that teaching strategies that emphasize passive learning should be discouraged and that children cannot be expected to “simply sit down and study.”

Reading a text without discussing it, debating it, or attempting to relate it to real-world situations is an example of passive learning. Instead, instruction based on Piaget’s theories stresses the idea that kids learn best through interaction. Here are a few instances:

- Physical engagement (e.g., seeing and touching insects when learning about them)

- Verbal communication (e.g., talking about how new learning material connects to everyday experiences)

- Interaction that is purely abstract (such as pondering novel concepts, debating complex or difficult issues, or acting out concepts, ideas, or people)

Play Theory

According to Piaget (1951), play is essential for children’s learning. Assimilation is exemplified through play, and accommodation is exemplified by imitation.

Based on their stage of cognitive development, he suggested that youngsters can play one of three different sorts of games:

- Playing drills

- Game symbols

- Rules-based games

Practice games include repeatedly doing a specific set of actions for purely recreational purposes. These practice games may not seem like much, yet they are crucial for cognitive development.

Symbolic games occur in the preoperational stage and feature make-believe settings and characters.

Later, at the concrete operational stage, rule-based games start to arise. These games feature abstract components as well as rules and penalties for breaking them.

Classroom / Session-based Games

It’s critical to adapt classroom activities to the kids’ overall developmental stage.

The finest classroom activities for very young children in the sensorimotor stage focus on repetition and exciting outcomes. In these activities, the kid frequently exhibits a newly acquired skill or behavior, rewarding the behavior. Examples include kicking leaves, rattling toys, splashing water, and playing musical instruments.

Games in the classroom that include imitation are effective strategies to introduce new ideas to kids who are still in the preoperational stage. Children can learn about animals, for instance, by acting like them (e.g., “roar like a lion,” “jump like a frog”).

By simulating various social circumstances, such as pretending to be a merchant, children can also learn about social relationships and interpersonal skills. Children can also play symbolic games by imagining that one object is another, such as when they pretend that a stick is a lightsaber.

Games with rules are better suited for older kids. Because they promote decentering, these games can be used to teach ideas like the theory of mind.

For instance, in “Simon Says,” kids are taught to watch the teacher and understand that if they don’t do as they are told, they will be kicked out. Young children typically do not comprehend games with rules and do not perform well with counting or numbers.

This is the reason, for instance, that very young children do not comprehend the ‘Musical Chairs’ penalty for one child. If the penalty is eliminated and the chairs remain the same, little children will love the game.

Games can also help students learn by letting them choose their own rules. When kids play unstructured without the teacher’s guidance, there should be fresh toys connected to the ideas they’re learning about.

Chapter 6:

Comparing Piaget’s Model with Other Development Models

An established model like this would make less sense if it does not have relevant critiques.

And it is of course always in our best interest to understand these critiques to have a holistic understanding of this theory.

Differences and Similarities in Piaget’s Models and other Models of Child Development

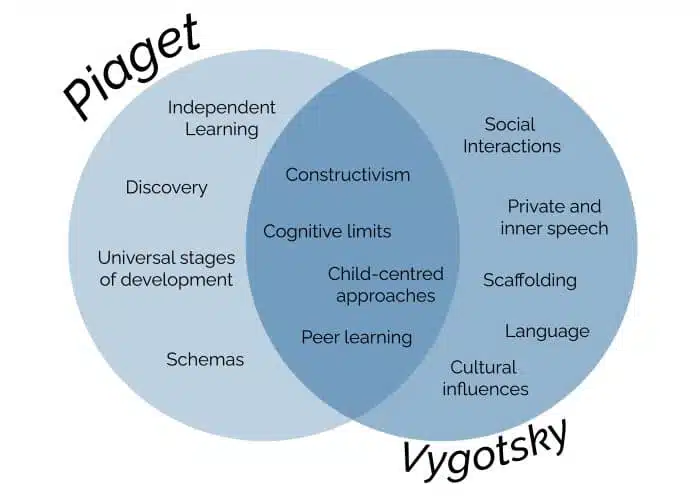

Piaget’s theory of cognitive development is one of several theories about how children develop. Other contrasting theories include Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory, Freud’s psychoanalytic theory, and importantly for this post, Erikson’s psychosocial theory of development.

However, the most relevant of these theories is Erikson’s and we are only going to focus on that one.

Differences

Erikson prioritized healthy ego development as opposed to Piaget, who concentrated on cognitive growth. People who successfully deal with particular personality disorders at predetermined points in their life create healthy egos.

Particularly, two opposing personality traits—one positive and one negative—define each growth stage. Successful resolution happens when one positive characteristic is stressed more than the other, leading to the growth of a virtue that promotes the healthy resolution of succeeding stages.

For instance, children feel both trust and mistrust between the ages of 12 and 18 months. They will acquire the virtue of “hope” if they manage to get through this crisis by striking a good balance between trust and suspicion.

Eight personality crises in total, five of which start before the age of 18, were hypothesized by Erikson:

- Basic trust against mistrust (0–12–or–18–months)

- Shame and doubt against autonomy (12/18 months to 3 years)

- Effort versus guilt (3–6 years)

- Industry vs. ineptitude (6 years–puberty)

- uncertainty between identities (puberty–young adulthood)

Not all of Erikson’s theory’s developmental phases line up with Piaget’s suggested cognitive phases. For instance, Erikson’s theories’ second and third phases and Piaget’s preoperational stages coincide.

If you want to dwell deeper into the contributions of the founders of child development theories, I recommend you to check out this informative article, Vygotsky, Erikson, and Piaget and Their Contributions to Education.

Similarities

Erikson, like Piaget, emphasized that children’s development happens through interaction with the outside world, but Erikson’s stages place a greater emphasis on societal influences.

Children are active participants in their world, and Piaget and Erikson both highlighted that development happens in stages.

Other than Erikson, another prominent psychologist at the time was Vygotsky. Lev Vygotsky, another key contributor to the field of child development, varies with Piaget’s theory in a number of significant respects.

Although Vygotsky recognized the importance of curiosity and participation in learning, he placed more emphasis on society and culture.

Vygotsky thought that people (such as parents, caretakers, and peers) and external elements (such as culture) have a bigger role in development than Piaget did. Piaget believed that development is mostly driven from within.

Conclusion

Congratulations, as always, for sticking with me through the entire article! Now, you are much better equipped to coach young children.

But more importantly, what can you do the next time you explain anything to a youngster knowing that their cognitive development restricts their capacity for learning and understanding?

- Use straightforward, kid-friendly examples.

- Explain ideas simply while taking into account the constraints of each cognitive stage.

- Encourage conversation and imagination to produce memorable interactions and experiences.

Most importantly, keep in mind that kids are not “mini-adults” when they are born.

They do not have adult cognitive capacities, and they do not have the lifetime of experiences for these abilities to grow.

Instead, kids must actively engage with their environment and the people that live there in order to learn. For learning to take place, individuals must be exposed to new situations and knowledge, and more significantly, they must be given the chance to fail.

I hope you enjoyed reading this article as much as I enjoyed writing it. Now let me ask you:

Which section of the article did you find the most interesting?

Which child development theory is the best according to you?

Was there anything I missed out?

Let me know your thoughts in the comment section below.

Download a FREE PDF version of this guide…

PDF version contains all of the content and resources found in the above guide.

ABOUT SAI C.N.G. BLACKBYRN

I’m Sai C.N.G. Blackbyrn, better known as “The Coach’s Mentor.” I help Coaches like you establish their business online. My system is simple: close more clients at higher fees. You can take advantage of technology, and use it as a catalyst to grow your coaching business in a matter of weeks; not months, not years. It’s easier than you think.

AS SEEN ON

0 Comment